Measles cases in 2013 in the United States are already amongst the highest they’ve been in any year since 2001, according to the most recent report from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). [1] The Americas eliminated measles in 2000, but the virus continues to be imported from regions where measles still circulates, either through residents returning from travels abroad or from visitors. About half of the measles cases in the US this year originated in Europe.

The latest CDC article discusses 159 cases, nearly two-thirds of which are linked to three outbreaks in communities “with pockets of persons unvaccinated because of philosophical or religious beliefs.” One of the outbreaks – 58 cases – is the largest single outbreak in the United States since 1996, and occurred amongst an orthodox Jewish community in Brooklyn. The second – 23 cases – was in a “largely unvaccinated religious community” in North Carolina. A third large outbreak of 21 cases occurred in Texas, and has been linked to a church community.

The CDC reports that the majority (82%) of the 159 people infected by measles were not vaccinated- most of those because of philosophical or religious beliefs. About 13% were babies under one year of age who are too young for measles vaccination (according to the American vaccination schedule).

These outbreaks are costly to human health and health systems. In Brooklyn, health workers spent time identifying about 3,500 people in health clinics, hospitals, schools and homes who may have been exposed. One child had pneumonia. Two pregnant women were hospitalized, and one miscarried. North Carolina estimates the outbreak added 2200 hours of work for state and local health agencies. In the affected county in Texas, health workers provided extra immunization clinics, epidemiologists investigated the outbreak, and public information officers handled dozens of media requests. In total, 17 people had to be hospitalized.

What are the lessons from these cases? Experts stress that it’s not an issue with specific religions, but pockets of vaccine refusers within these communities. The CDC reports, for example, that the orthodox Jewish community in Brooklyn had high vaccination coverage.

Dr Jeffrey Duchin, the incoming chair of the Infectious Diseases Society of America’s Public Health Committee says: “Virtually no major religion prohibits vaccination, yet 19 US states allow personal belief exemptions from childhood vaccines and almost all states allow religious exemptions. In Washington State this past school year, only 3% of exemptions were claimed for religious reasons, while approximately 70% were for personal/philosophical reasons. Even though almost no religions actually prohibit vaccination, followers of certain religions or religious leaders may share anti-vaccination beliefs that are not, however, based in the religion.”

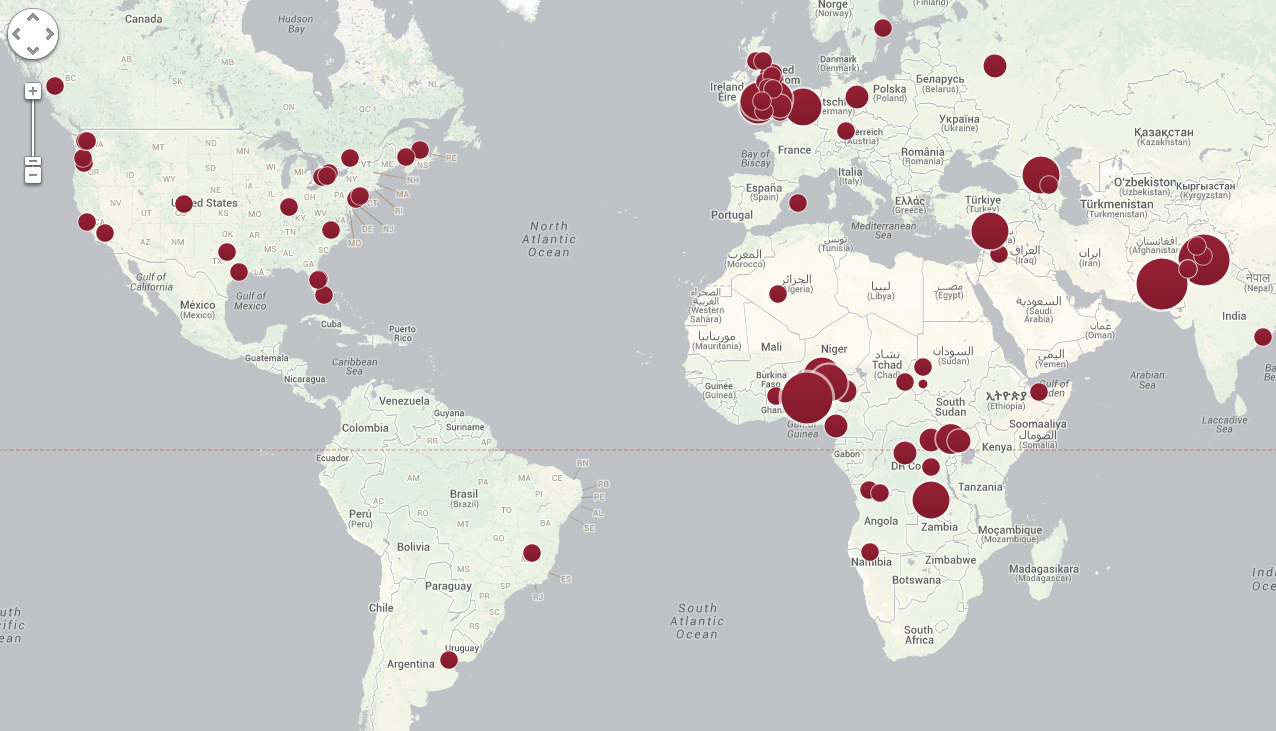

The real problem is that measles is one of the most infectious viruses known to humankind, and people who aren’t protected, have a high risk of infection. “Measles is still common in large parts of the world. With international travel outside of the Americas we should expect some people to come into the country with the disease. When measles is introduced into a ‘pocket’ of people who are not immune, an outbreak is going to happen,”says Dr. Anita Kurian, the Associate Director of Tarrant Country Public Health in Texas.

“Unvaccinated people tend to cluster geographically and these clusters are often associated with disease outbreaks. There are several such areas in the U.S. and outside the US,” says Dr Saad Omer, Associate Professor Global Health, Epidemiology, and Pediatrics at Emory University.

“Unvaccinated people tend to cluster geographically and these clusters are often associated with disease outbreaks. There are several such areas in the U.S. and outside the US,” says Dr Saad Omer, Associate Professor Global Health, Epidemiology, and Pediatrics at Emory University.

Dr. Duchin adds that “Even small numbers of persons unvaccinated against measles in highly vaccinated countries like the US can spark outbreaks both among like-minded unvaccinated community members but also pose a threat that can spread the disease to others in the community who did not chose to be unvaccinated, but cannot be because they are infants, have underlying illness or take medication that weakens the immune system, or are pregnant.”

Dr. Ruth Lynfield, the outgoing chair of IDSA’s Public Health Committee, compares the outbreaks this year to a 2011 outbreak in Minnesota originating in a Somali community and spreading to 20 people. “Although this particular outbreak was linked to the Somali community, the refusal to get vaccinated was not because of religious beliefs, but rather vaccine safety concerns.”

The measles vaccine, licensed fifty years ago, has been proven safe and effective, and two doses result in more than 95% protection. It has prevented millions of deaths worldwide. However public concerns still linger and rumors circulate. Public health authorities must continue to work to understand the root causes of vaccine fear or rejection, and invest in strategies to help overcome these.

In Texas, Dr. Kurian says that “some of the concerns we have… include fear of the vaccine itself, the number of vaccinations given, and the belief that the disease itself is not something to fear.” She says that several strategies must be used to help encourage vaccine acceptance. “Continuing with awareness campaigns to keep immunization rates high is a maintenance issue with a good return on the effort. The recent measles outbreak most likely would have been larger had the general population, (including probably many at the affected church) not had a high rate of immunization.”

Dr. Omer also says boosting vaccine confidence requires a multifaceted approach. “Maintaining public confidence in vaccines by conducting robust vaccine safety surveillance, enabling healthcare providers to effectively communicate with parents regarding vaccines, and effective messaging to parents that focuses not only on whether or not a specific adverse event is associated with vaccination but also discuss the risks of non-vaccination.”

“Many parents choose vaccination when their healthcare provider takes the time to explain why vaccination is important and strongly recommends it,” Dr Duchin explains. “Community leaders like religious leaders also need to take some responsibility and accountability for protecting their congregants and improving their health instead of increasing their risk for illness.

As of last week, all six World Health Organization regions, or 194 countries of the world have resolved to eliminate measles by or before 2020. The Americas are still free of endemic measles, as are most countries in the Western Pacific. Measles deaths globally dropped 71% from 2000-2011 due to country efforts to vaccinate children, many with support from the Measles & Rubella Partnership. However, large measles outbreaks continue in many countries in Europe, Africa, the Middle East and South-East Asia. In 2011, an estimated 158,000 people, mainly children, died of measles.

Given the susceptibility of even small communities in highly vaccinated regions and the constant risk of the measles vaccine “traveling” between communities, investing in strategies to help communities understand and demand vaccination is critical for success in measles elimination.

It is often assumed that the “last mile” of measles and rubella elimination/eradication will be traveled in a developing country,” Dr Omer concludes. “However, these recent outbreaks demonstrate that we cannot take developed countries for granted.”

[1] See the CDC’s Mortality and Morbidity Weekly Report published September 13 for three articles about measles in the United States including a review of total cases in the US, in a religious community in Brooklyn, New York; and in North Carolina.

Prelude Version 2.3.2

Prelude Version 2.3.2